Together with Dereje Feyissa, I have written an article entitled "Mbororo (Fulɓe) Migrations from Sudan into Ethiopia" (Dereje and Schlee 2009). That form of publication requires discipline in terms of both length and thematic focus. Inevitably, much of the detail and immediacy of the ethnographic observation got lost in that process. Therefore, I have decided to circulate a fuller set of data on the internet, a procedure which allows to include a greater number of tables, maps, and pictures. The present description follows closely the field diaries that I kept between 1996 and 2002 and, thus, provides deeper insight into my earlier research on Fulɓe. From 1996 to 1998, that research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and part of a project entitled "Ethnicity in new contexts: emergent boundaries and pluri-ethnic networks in the east of the Republic of Sudan" (Schl 186/9-1).

Publications in form of journal articles and books rarely permit a rich presentation of data. Much of the 'voice' of the interlocutors in the field gets lost in the process of interpretation, condensation and generalisation. Professor Al-Amin Abu-Manga and I have therefore decided to put full transcriptions and annotated translations of interviews we did on local history and the reshaping of ethnicities along the Blue Nile since 1996 online, so that other researchers can make use of them – be it for their readings of history or for linguistic studies of Fulfulde (Fulɓe language) or dialectal Arabic.

The oldest of the texts presented here was an interview in Sudanic Arabic which I conducted with Al-Almin’s younger brother Anwar in Damazin in 1996. I transcribed and transliterated it myself and translated it with his help. In 1998 Al-Amin himself took me on a trip up the Blue Nile and I could greatly profit from his contacts, his historical knowledge and his fully professional linguistic as a professor for African languages.

Everything which is in Fulfulde in the following texts has been transcribed and translated by Al-Amin as my notions of that language are very vague indeed. He also did a number of interviews in Fulfulde alone. When it comes to Sudanese Arabic, we maintained the three-column presentation I had used earlier: from right to left transcription in Arabic characters; transliteration in Latin characters; English translation. Many Sudanese are not used to read transcriptions from their language in Latin characters and regularly confuse the sounds represented by the Latin alphabet with English spelling conventions which are multifold, inconsistent and defy any logic, and have only vague correlations with the original sound values of the graphemes they use (e.g., 'nite' [like in 'ignite'], 'night' and 'knight' all stand for the sound shape [e.g., 'nait']). And no-one can tell whether a Sudanese who writes /oo/ in an SMS message means a long /o/ or a long /u/. Sudanese without linguistic training might therefore find the column in Arabic characters much more enjoyable to read. In this column also some distinctions have been preserved which have got lost in the pronunciation. In certain contexts, ق (q) and ك (k), for example, have collapsed into k in Sudanese pronunciation. Sudanese still might make the distinction, however, when writing their dialect in Arabic characters, and thereby increase the recognisability of some words for people familiar with Standard Arabic. For people whose first language is not Arabic, the middle column might be the straightest way to get to the actual pronunciation of what has been said. Not the least important reason for this is that in a Latin transcription all vowels are represented which is something Semites tend not to do. The two columns therefore fulfil different functions, give different information and therefore complement each other.

In our Latin transcription we have used English consonants and Italian vowel value. This combination allows a good approximation to a proper rendering of most words in most languages. For consonants which do not exist in English we have adopted the established English conventions for rendering Arabic sounds like kh for خ, the alveolar fricative, or q for ق, the emphatic /k/.

One note is necessary about content: we decided to omit all references to slavery or the former slave status of people, even vague ones like (unnamed) former slaves who were said to live in a certain (but unnamed) part of the village. Former slave status is a major concern to Sudanese, but it is a matter they discuss in secret. As a tribute to political correctness we have therefore excluded one entire interview which was just about slave descent and shorter references to slavery in other interviews.

The reader should thus bear in mind that these interviews do not present a mere reflection of reality. Like all interviews they reflect interests and biases. The most systematic bias, which we regret, is that all references to slavery had to be cut out. Contrary to anthropological conventions the names of the people appearing in the interviews are real. Our interview partners were notables and local (non-academic) historians and might have complained about us neglecting their intellectual rights if we had given them pseudonyms to hide their identities. However, where I describe own observations, some names have been replaced by names from the same language which a similar meaning or background (e.g., Biblical names by other Biblical names, etc.) for combining anonymity with as much preservation of ethnographic information as possible.

Furthermore, the names of the places mentioned in the original interviews were not changed. Indeed, going deep into local history makes little sense if the reader is not allowed to know which place is talked about. The interviews by now are almost fifteen years old, the older seventeen, and as the slavery issue has been cut out anyhow, we can be reasonably sure that putting these texts online does not affect anyone’s personal interests and feelings. Apart from that there are limits to adjusting what one says to what people like to hear. Political correctness needs to be balanced against truth.

Even after reading this documentation, the non-specialist reader may find that the interviews presented here lack context. These documents take him or her straight into an unfamiliar setting in company of someone who talks to him or her in a strange language. May I therefore point to some publications which contain some of the introduction information which may be found lacking here. These publications are based partly on the material collected here and partly on other materials. On Fulɓe, their internal diversity and their relations with other ethnic groups, the reader may refer to:

Dereje Feyissa, and Günther Schlee. 2009. Mbororo (Fulɓe) Migrations from Sudan into Ethiopia. In: Günther Schlee and Elizabeth E. Watson (eds.). Changing Identifications and Alliances in North-East Africa. Volume II: Sudan, Uganda, and the Ethiopia-Sudan borderlands. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 157-178.

Diallo, Youssouf, and Günther Schlee (eds.). 2000. L’ethnicité peule dans des contexts nouveaux: la dynamique des frontières. Paris: Karthala.

Osman, Elhadi Ibrahim. 2008. The Pastoral Fulbe in the Funj Region: a study of the interaction of state and society. Khartoum: University of Khartoum, Faculty of Economic and Social Studies, Department of Social Anthropology and Sociology, PhD thesis.

Osman, Elhadi Ibrahim. 2009. The Funj Region Pastoral Fulbe: from 'exit' to 'voice'. Nomadic Peoples, 13 (1): 92-112.

Osman, Elhadi Ibrahim, and Günther Schlee. 2014. Hausa and Fulbe on the Blue Nile: land conflicts between farmers and herders. In: Jörg Gertel, Richard Rottenburg and Sandra Calkins (eds.). Disrupting Territories: land, commodification & conflict in Sudan. Woodbridge: James Currey, pp. 206-225.

Schlee, Günther. 1997. Ethnizitäten in neuen Kontexten: urbane und hirtennomadische transkontinentale Migranten (Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Benin, Kamerun, Sudan). Working Paper No. 282. Bielefeld: University of Bielefeld, Faculty of Sociology, Sociology of Development Research Centre.

Schlee, Günther. 2011. Fulbe in wechselnden Nachbarschaften in der Breite des afrikanischen Kontinents. In: Nikolaus Schareika, Eva Spies and Pierre-Yves Le Meur (eds.). Auf dem Boden der Tatsachen: Festschrift für Thomas Bierschenk. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, pp. 163-195.

Schlee, Günther, and Martine Guichard. 2007. Fulɓe und Usbeken im Vergleich. In: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Bericht 2007 (Abteilung I: Integration und Konflikt). Halle/Saale: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, pp. 11-53.

About Maiurno and the professional specialisations of the Fulfulde and Hausa speakers living there, Al-Amin Abu-Manga has written the following article:

Abu-Manga, Al-Amin. 2009. The Rise and Decline of Lorry Driving in the Fallata Migrant Community of Maiurno on the Blue Nile. In: Günther Schlee and Elizabeth E. Watson (eds.). Changing Identifications and Alliances in North-East Africa. Volume II: Sudan, Uganda, and the Ethiopia-Sudan borderlands. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 139-156.

We hope to make more use of this material in the future but at the same time we are sure that our lives will not suffice for analysing it from all possible perspective. Further we love to do field research and will therefore, so Gods wills, collect yet much more material which will probably also remains underutilised. The reader is therefore welcome to cite this material and to use it for every legitimate purpose which he or she sees it fit.

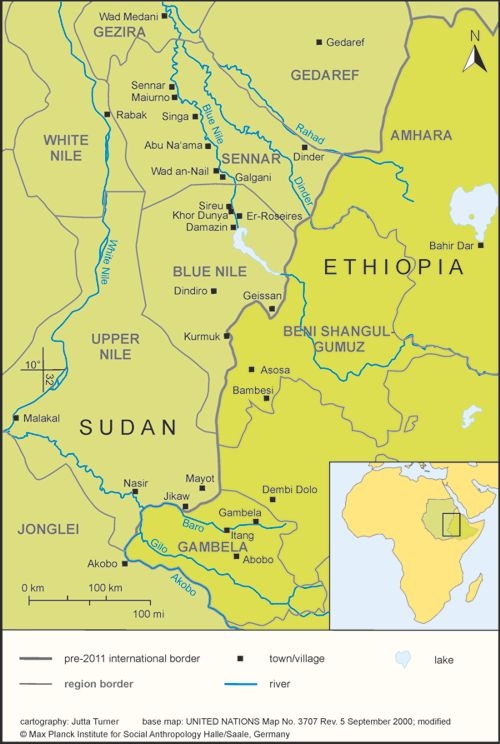

Map 1: The research area