In the morning, sent e-mails from the UNHCR office to my secretary and my wife.

Concerning the report "Interethnic Relations in Gambella: Field report" by Dereje (p. 51): "While commenting on Anuak-Nuer relations, Obong said, we are few in number. There is the culture of family planning among the Anuak. We could make children only after 3 years." The discourse of the Anywaa about Nuer demography and migration pressure (reminiscent of the "Yellow Danger" discourse in Europe at the turn of the last century) has parallels in the Rendille-Somali relationship (see my paper on "Camel Management Strategies and Attitudes towards Camels in the Horn", Schlee 1988).

Gambella town, Ethiopia Hotel

Dereje has invited two local highlanders who have photographs and memories of "Fellata" (Mbororo), who have migrated back and forth from the Sudan to Gambella several times, over a period of years, sometimes with long intervals between various migrations. One of them is Amanuel, a photographer, who owns a studio here. The other one is Amtallaqa, a government worker from the Ministry of Agriculture.

Amtallaqa was taken to Cuba at the age of 14 after his father, who had volunteered to join the Ogadeen war (1977-1998), had been killed in action. Cuba had offered to train war orphans. Amtallaqa's sister also went to Cuba, where she received training as a pharmacist. Amtallaqa, who spent about seven years in Cuba (see also below), loves the Spanish language, which he has mastered, and is constantly looking for people with whom he can converse in Spanish. That is how he ended up talking with me for the whole evening, while Dereje was engaged in conversation with Amanuel. Amtallaqa's love for Cuba extends beyond the language to the leaders of the country and the martyr of the socialist revolution, Che Guevara. He was very pleased to hear that I, like many Germans of my generation, once Che's picture on my wall.

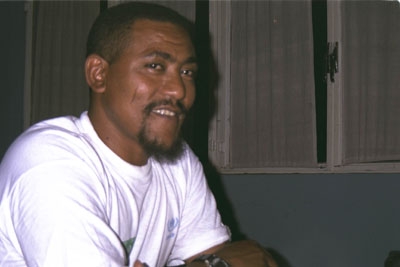

Amtallaqa

Move mouse over picture for larger version

"Fidel cuando habla por ocho horas lo puedo escuchar. Para mi el español es un idioma magnifico. Se pueden expresar todos sentimientos. Tengo unos libros en español. Unos [de ellos] los he leído ya diez veces. Ahora no tengo nada [de nuevo]. Nada mas que repetir lo que tengo. Uno de los libros es Fidel y la religión."

This hunger for the Spanish language, which leads Amtallaqa to read the small number of books he owns over and over, and his longing for the Cuban way of life and the socialist idea of friendship of peoples seem to be strong forces in his life. "[Para Cuba] tengo un amor que nadie puede borrarlo."

Amtallaqa spent the period from 1978 to 1985 in Cuba, where he was trained in nutritional chemistry. Then he joined the Ethiopian public service. Much later, in 1997-1998, he had another experience abroad: he spent four months at the Agricultural University Wageningen, Netherlands, on a grant from the European Community in the framework of the LFDP, the Lake Fisheries Development Project. He may have had an affinity to fishing in lakes because he grew up in Bahar Dar on Lake Tana, where his father, before he went to war, was the director of something that I neglected to write down.

From his various periods abroad he remembers funny incidents when people refused to believe that he was an Ethiopian. In fact, his excellent Spanish and his features, which look Native American with some African elements, make one think, rather, of a South American.

Amtallaqa does not have connections to Gambella pre-dating his transfer here as a Government officer. He is married and has four daughters. Two daughters have Ethiopian names, another is called Tamara, after Che’s girlfriend, and a fourth bears the Spanish name Linda.

Amtallaqa’s interest in the "Fellata" who came here might be seen in connection with his socialist internationalism and his general interest in foreigners. After the change of government in 1991 he stored the equipment of a Japanese anthropologist in his house for a whole year, until the anthropologist found it safe to come back to Ethiopia. Amtallaqa is full of stories about other foreigners he has met.

Some of the "Fellata" speak Oromo, as I discovered to my delight when, several years ago, I met a group of them – possibly the same ones whom Amtallaqa had already met – near Abu Na’ama in the Sudan. Unfortunately, Amtallaqa does not speak any Oromo, and the "Fellata" spoke neither Amharic nor Spanish. In the late 1990s, he hosted them in his house and became good friends with them, especially with a certain Usman, who gave him a bow and a quiver full of arrows. When we met with Amtallaqa, he brought the bow and quiver, which are shown in the photograph below. (Others had tried in vain to purchase such items from the Mbororo.) Communication between Amtallaqa and "Fellata" appears to have been very basic. He has no information about the migration routes of the Mbororo. He says that they migrated through various countries on "the Horn of Africa" and even went as far as Kenya, which is clearly wrong. He does not know any of their section names or any other information that might be useful in finding out to which particular group of Mbororo he had contact.

The last time "Fellata" were here was in 1997-1998. They stayed for about a year. This was the only time that Amtallaqa had contact with them. They had a single headman, "un solo jefe".

The provincial administration tried to send them back to the Sudan; but the local population was afraid to help implement this policy, because the Mbororo were believed to have magic ways to defend themselves. "Tienen que salir pero la gente local no presionan mucho porque saben que tienen magica."

Mbororo bow and quiver with

arrows, brought along by Amtallaqa.

Move mouse over picture for larger version

As far as visual features are concerned, Amtallaqa noted the preference of Mbororo for the colour blue, which is also illustrated by the photographs he had brought along. "Un vestido muy azul. Los hombres vestieron azul."

The economic activities he recalls include the sale of milk and butter by Mbororo women. ("Las mujeres venían a vender mantequilla, leche.") Through the sale of cattle for slaughter, which is a male activity, the Mbororo alone met the entire local demand for beef. ("Los hombres venden vacas, bueyes, toros. Por un tiempo se consumía nada mas que la carne de ellos.")

Amtallaqa has a number of stories about Mbororo magic. Once a "Fellata" he met in a bar mistook him for a military officer (his nickname 'Amtallaqa' refers to a military rank, approximating that of lieutenant). The owner of the bar had been a prisoner of war in Somalia for 11 years and had learned some Arabic. The two managed to play a joke at the expense of the "Fellata". Amtallaqa demanded a bribe for allowing the "Fellata" to stay. The "Fellata" asked him what it was that he wanted, and Amtallaqa asked for a love charm. The "Fellata" removed various kinds of medicine from their plastic wrapping and instructed Amtallaqa to rub his body with this mixture after bathing on three subsequent Fridays. Later, he tried the medicine to see if it was effective. Even married women agreed to go with him for the mere asking. He then became afraid (of disturbing the social order?) and threw away the remainder of the medicine.

(A proper testing procedure would, of course, also require making the same proposition to women without the love charm. This, Amtallaqa might never have dared to do. We can therefore not exclude the possibility that the women in question were just responding in their usual way.)

In another incident, somebody had insulted a "Fellata" in Oromo by calling him an "animal" ("bines"?). The offended "Fellata" took two nails, the length of Amtallaqa’s finger, out of his pockets and inhaled them through his nostrils. He then threatened to retrieve them through the penis of his offender. The latter did not delay in eating his words and in clarifying that the "Fellata" was by no means an animal. He was thus saved from having to endure the procedure.

On another day, a Mbororo woman came to Amtallaqa’s office. He gave her three Birr for tea. She asked him whether she could help him in any way. He replied that his wife had continuous pain in her left breast. The woman left, and Amtallaqa’s wife never had any pain of that sort again.

Am Nebentisch waren fünf Nuer mittleren Alters und eine weiße Frau. Die Nuer waren in den USA eingebürgert und waren jetzt zu Besuch zurückgekommen.