Abu Na’ama

Elhadi, a young lecturer at the University of Sennar (see in the meantime Osman 2008 and 2009), Abu Na’ama, tells me about Saaleh Bank, a Mbororo leader who was killed three months ago near Malkan, in the Funj region, by the SPLA. That was before Geissan was recaptured from the SPLA by the GoS.

Saaleh Bank had three wives, one in Mazmum, one in Boot, and one with the cattle. He had fought more than a hundred battles. He was rich in cattle. He loved war. The GoS supported him. The opposition accused him of killing civilians. The Government knew about his death before the news had spread locally. This shows how much the GoS depended on him.

Harun Bello told Elhadi that the Mbororo hold the GoS responsible for the death of Saaleh. They did not give him sufficient logistical support, failing to supply him with the necessary ammunition and water, for example. Recently, after the occupation of Torit by the SPLA, the GoS wanted to recruit mujaahidiin among the Fellata to recapture that Equatorian town. This request was at first denied. In the end, 50 fighters were named reluctantly.

At this point, I depart from the chronological order and continue with more information on Saaleh Bank. He appears to be a legendary figure. On the evening of October 2, in a camp west of Khor Dunya occupied by Woyla, another nomadic Fulɓe group, a man who has just come back from the fighting reported how Saaleh and his group ran out of water and were encircled. He insisted that there was no bullet hole in Saaleh’s body, but that he was struck down by the explosion of a bomb. This appears to be important, because of the belief that he was “bullet proof” as a result of some magic – which, of course, is of little help if one is killed by the impact of something other than a bullet.

Back to my notes on September 25.

Religious practices: Others have described the Mbororo as less literate and less well versed in Islamic practice than other Fulɓe cattle nomads (see the interview above with Abdullahi Muhammad Sa’id al-Qarawi, March 14, 1998, who contrasts Mbororo with Jaafun, Booɗi and Duga). Therefore, I ask Maahi Bello about religious instruction for the children. He says there is a khalwa (Qur’anic school) with a Qur’anic teacher named Faki Muhammad, a Mbororo. (It seems to be some distance away, since we do not hear or see anything of it later in the night.) The grown-ups in this group cannot read or write. He knows some suras by heart. The children do not know much about reading and writing either, but they have made a start. The other tribes in the area (I ask about Jaafun, Booɗi, and Duga) are roughly on the same level. Some individuals are literate, others not.

A middle aged man – the youthfulness of his face is somewhat contradicted by the white stubble of the beard surrounding it – carries a whole bundle of hiyaab around with him. Some of these leather pouches with Qur’anic writings sewn into them – the Somali would call them hersi – are pretty big, almost the size of an A6 pocket calendar. I ask him why he carries so many. He has inherited two of them from his father.

He seems to be proud of his knowledge about medicine and magic. He draws our attention to the man next to him who is uttering magical formulas over a rope, which is meant to protect a cow from miscarrying.

The middle aged man does not seem to like Sheikh Baabo ʿUmar. He tells me that Sheikh Baabo was rejected and "got lost to Khartoum" (waddar lee al-Khartuum). He might look for some other occupation there.

Diseases and parasites: According to ʿAwad, miscarriages in cows can be caused by brucellosis. He believes this disease to be widespread here. Not only the frequent miscarriages among cows, but also the symptoms about which many people complain (fever, headache) support this assumption.

Near the path, I see a heap of human faeces that is full of large worms. Repeatedly, ticks have to be removed from my body.

ʿAwad is surprised that the Mbororo care little about diseases. Several of the Mbororo visitors at the market in Wad an-Nail told him that they felt sick, but they had not sought medical care or even gone to a pharmacy. Several of Maahi’s children are suffering, presumably from malaria.

In the genealogies that I have collected (see below), no mention is made of children who have died, and birth spacing looks suspiciously regular. But there must be considerable child mortality.

Composition of the settlement: I collect some genealogical data, then ask where the people mentioned are living. Then I proceed the other way round, listing the houses which are visible from where I am sitting and asking who is living there and how they are related to the others, in order to get some rough ideas about residential and marital patterns and group composition.

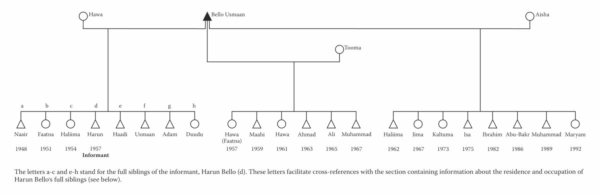

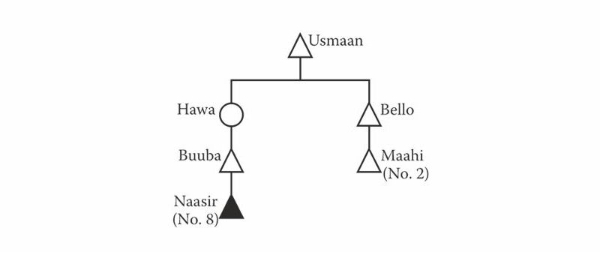

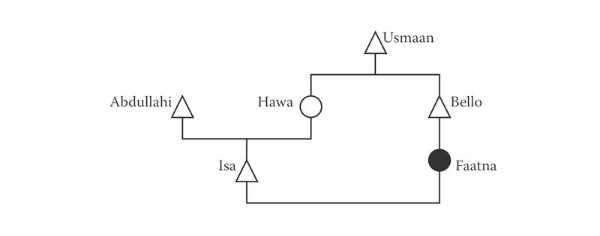

Fig. 2: The father of Maahi and Harun, the late Bello Usmaan, and his wives and children

click to enlarge

The first summary statements, according to which all of Bello Usmaan’s children were in the same area and staying with the cattle, was not quite true for this set of full siblings, the only one for which data about residence and occupation was gathered systematically.

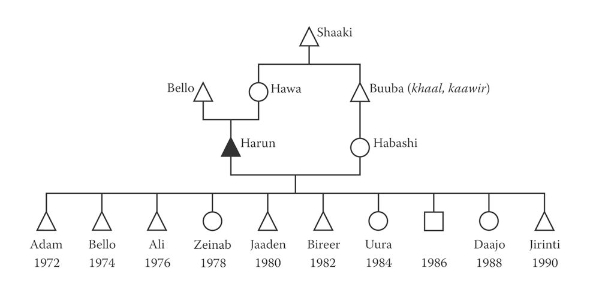

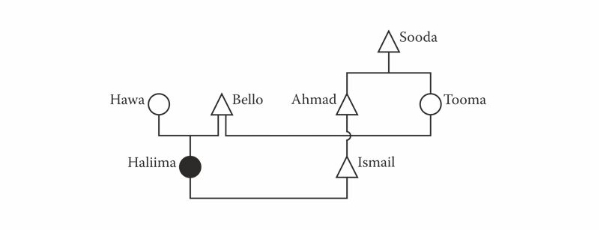

Fig. 3: Harun Bello’s own family

click to enlarge

Harun has only one wife. He was 15 when he got married. As the diagram shows, his wife is the daughter of his MB (khaal; Fulfulde: kaawir). All his children are in the area and occupied with the cattle. The first four of them are married. Adam has a child of three years; the others do not have any children yet.

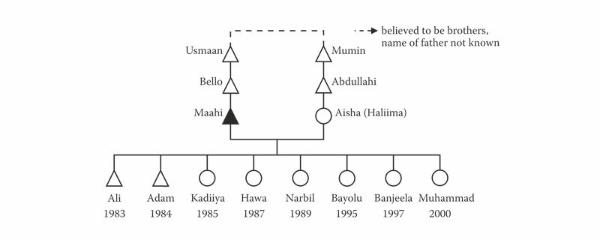

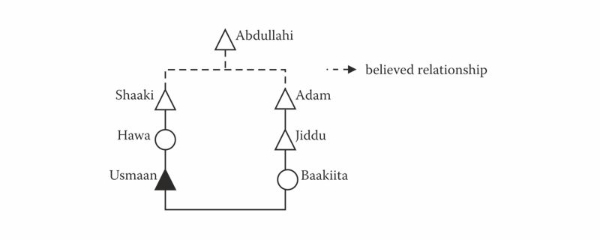

Fig. 4: Maahi Bello’s own family

click to enlarge

Usmaan and Mumin, the FFs of the couple, are believed to be brothers, which would make Maahi and Asha wad amm/bitt amm (i.e., patrilateral parallel second cousins) to each other.

The name of the putative shared father of Usmaan and Mumin is not remembered.

Chronological clues for estimating the children’s years of birth were the construction of the highway to Damazin, 1990, and the attack on Kubri Yabus, 1995.

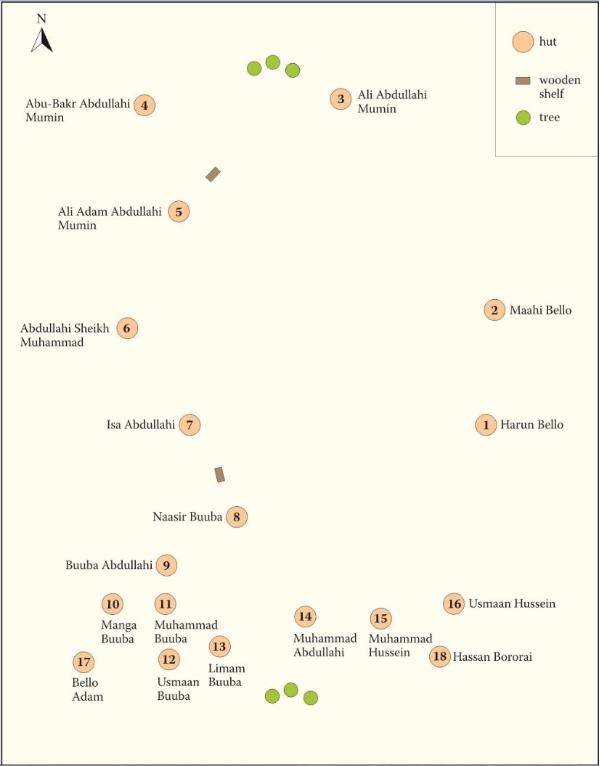

(Sketch) Map 7: The neighbourhood of Maahi and Harun Bello

Relationships between the households:

No.1, Harun Bello, is a half-brother of No. 2, Maahi Bello.

No. 2, Maahi Bello, is married to Asha, daughter of No. 3, Ali Abdullahi Mumin.

No. 3, Ali Abdullahi, and No. 4, Abu-Bakr Abdullahi, are FBs of No. 5, Ali Adam.

No. 5, Ali Adam, is married to Hawa, sister of Maahi Bello, No. 2.

No. 8, Naasir Buuba, is FZSS of Maahi Bello, No. 2.

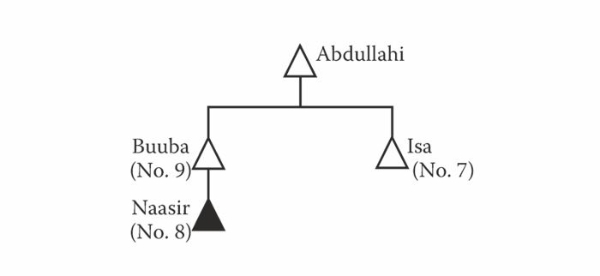

Fig. 5: Kinship relationship between households No. 8 and No. 2

click to enlarge

No. 8 is FBS of No. 7, Isa Abdullahi.

Fig. 6: Kinship relationship between households No. 8 and No. 7

click to enlarge

No. 9, Buuba Abdullahi, is the father of No. 8. His other sons (No. 10, No. 11, No. 13 and No. 14) are located behind him (from Maahi’s house, near which the ethnographer was sitting, to the south).

No. 9, Buuba Abdullahi, is FZS of No. 1 and No. 2.

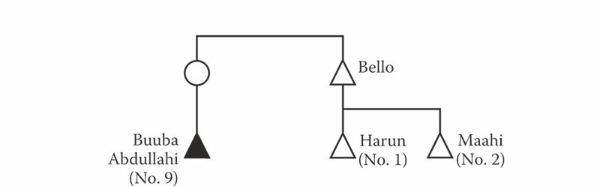

Fig. 7: Kinship relationship between household No. 9 and households No. 1 and No. 2

click to enlarge

Residence and occupation of siblings: I then ask Harun about the residence and occupation of his full siblings. He cannot give me the same information about his half-siblings and other sets of siblings with any certainty, but as systematic questioning is a bit tedious, I decide that it has been enough for one evening and let free conversation take its course. The letters a-c and e-h refer to fig. 2 above (Bello Usmaan, his wives, and their children)

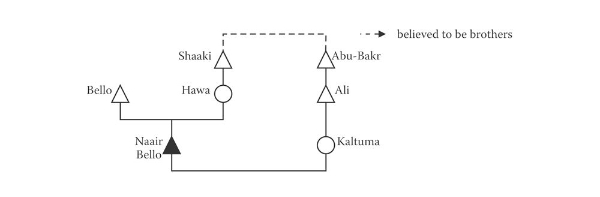

a) Naair Bello lives a bit further north, beyond the trees. His first wife, Tooma, is said to be a remote patrilateral parallel cousin. In the case of his second wife, Kaltuma, as well, the relationship cannot be traced to named ancestors. Naair’s MF and Kaltuma’s FF are believed to be related somehow, which makes her a type of bitt khaal (MBD).

Fig. 8: Kinship relationship between Naair and his second wife Kaltuma

click to enlarge

b) Faatna is likewise living beyond the trees (further north). She is married to Isa Abdullahi, her FZS.

Fig. 9: Kinship relationship between Faatna and her husband Isa Abdullahi

click to enlarge

c) Haliima lives in Agade, south-west of Damazin. She is related to her husband, Isma’il, through the brother of a co-wife of her mother. This makes her husband a sort of wad khaal (MBS) to her. They are nomadic cattle pastoralists.

Fig. 10: Kinship relationship between Haliima and her husband Ismail

click to enlarge

e) Haadi Bello is now staying with his cattle at Kumai, near Agade. His wife, Asha Abu-Bakr, is Mbororo, but not a traceable relative.

f) Usmaan Bello lives in the Ingessana Hills. He is a sedentary farmer in a village. His wife, Baakiita, might be a matrilateral second cousin.

Fig. 11: Kinship relationship between Usmaan and his wife Baakiita

click to enlarge

The mother of Usmaan (and of his entire set of full siblings) is very old and can no longer move with this nomadic hamlet. For four years now, Usmaan has lived with her in the Ingessana village. Most of his cattle are here, but he keeps some milk cows for his household. The milk cows are exchanged for fresh ones from the nomadic herd each time the latter passes through the vicinity.

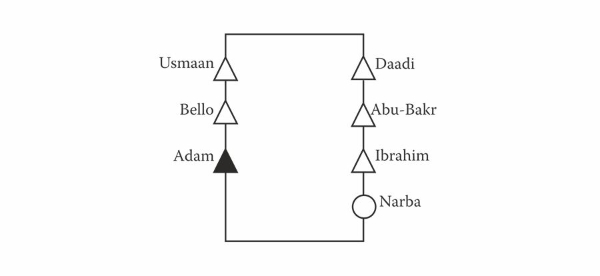

g) Adam lives next to his brother Naair (a). His wife Narba is his FFBSSD.

Fig. 12: Kinship relationship between Adam and his wife Narba

click to enlarge

h) Duudu lives close to here. She is married to Ali, a type of wad khaal through the co-wife of her mother, another mother so to say. The same figuration as c (see fig. 9 above).

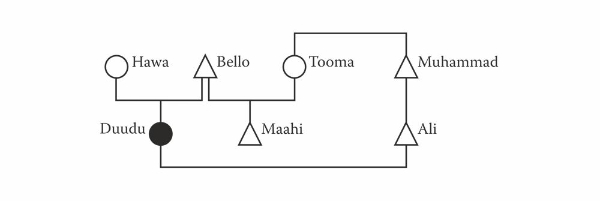

Fig. 13: Kinship relationship between Duudu and her husband Ali

click to enlarge

From the perspective of alliance theory (i.e., of the men involved), one can see this as a delayed exchange: Muhammad gives his sister, Tooma, to Bello, and the latter reciprocates by giving his daughter, Duudu, to Muhammad’s son, Ali.

From a female perspective one might theorize that such an arrangement limits rivalry between co-wives. Any parental investment of the shared husband in his children by a co-wife becomes more tolerable to a woman if, ultimately, a relative of her own benefits from these investments by marrying one of these children.