Location: Woyla hamlet west of Khor Dunya

After the greetings and some small talk under the shade tree, I mention that I have been to Qashmando (see entry from November 26, 2001). This immediately gets the attention of everybody there. When I mention the name of Muhammad Zakariya, the Woyla man I have met there, I am corrected: the man in question is Muhammad Jibriil. Our main interlocutor, Abu-Bakr Ahmad Jibriil says that Muhammad is his FB. The story fits: the man in question was separated from his group before the SPLA attack five years ago (they specify that it was after the first attack against Kubri Yabus in 1994 or 1995); he herds the animals of a rich Oromo; his Fulɓe family is in the Yabus area, etc. Certainly, there are not two Muhammads in the same group and with the same biography living in Qashmando (those who pointed him out to us described him as the only Pullo far and wide). For now, it is a mystery to me why I have Zakariya as his father’s name in my notes. Did he find it convenient in Ethiopia to affiliate himself with someone named Zakariya? Did I mishear the name?

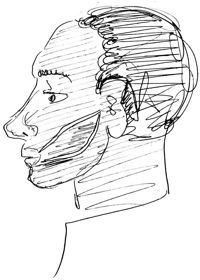

The men where we are all have two scars from apparently deep incisions from the corner of the mouth to the ears. I ask them whether all Woyla men have such scars. Muhammad in Qashmando did not appear to have any. The answer is in the affirmative. Muhammad has small scars such as these, too.

Portrait of a Woyla man

Move mouse over picture for larger version

My interlocutors report that there are SPLA attacks against them every year. In one year, there are ten dead and in another five, counting only the Woyla casualties. In the south, one can no longer be sure of ones life. At any time, one can be shot or deprived of ones cattle. Fellata are known for their ability to suffer without lamenting, but what can one say now?

Here, all along the Nile, Hausa have made gardens so that the cattle have no access to the water. Further south, in the Southern Blue Nile area of the Sudan (saaʿid), it is the same. In other places, the Woyla have to pay Arabs for water. But they cannot even rely on these sources. If they come a second time, the Arabs might refuse to sell them water.

In Ethiopia they received medicine for their cattle free cost. Here they have to pay for it. Sometimes a bull, sometimes small stock needs to be sold to cover these expenses.

Abu-Bakr has much linguistic agility. When I ask him in Oromo whether he speaks Oromo, he answers in Amharic, saying that his Amharic is quite alright but that he only speaks a little Oromo. He also has an English vocabulary of a few dozen words and phrases, although he did not go to school. It would not be enough for a conversation, but he demonstrates his knowledge of vocabulary by enumerating the words he knows. He also claims to speak Ingessana and Burun. Of course, I understand nothing of his demonstrations. That everyone here speaks fluent Sudan Arabic, in addition to their native Fulfulde, goes without saying.

The Woyla sheikh in Damazin is said to be Hassan Abu-Bakr Riiri. Muhammad in Qashmando had given another name: Suleymaan Bello. Muhammad might, of course, be referring to an earlier period.

A man named Idris Abu-Bakr Usmaan says that his younger brother, Muhammad Abu-Bakr, was with Muhammad Jibriil in Gambela. The group of Abu-Bakr Ahmad, our main interlocutor, went to Gambela-Begi-Qashmando for three years, but has not done so for the last seven years.

Not everyone here is a full-time herder. An elderly man, Usmaan Ahmad Saaleh, says he has a farm in Sinja Nabaag, near Damazin. There he has a wife, children and a part of his cattle. Here he has a junior wife, children, and more cattle. He came to the Sudan 30 years ago.

Ahmad Abu-Bakr explains three routes to seef pastures, one to the south, one to the south-west, and one to the west.

The route to the south:

| Place names |

Coordinates, if found on map(s) or located by GPS (+ waypoint No.) | Comments |

| Gamberda | ||

| Dunduru (Dindiro) | Lat. 11° 4' N / Long. 34° 7' 11" E | |

| Saali | ||

| Keeli (Kayli on some maps) | Lat. 10° 50' 42" N / Long. 34° 19' 26" E | The name means: "project belonging to a unit (of the army)". |

| Kurmuk | Lat. 10° 33' N / Long. 34° 17' E | |

| Khor Boodi | ||

| Deem |

The route to the west:

| Place names | Coordinates, if found on map(s) or located by GPS (+ waypoint No.) | Comments |

| Rooro | ||

| Jamam | ||

| Jirewa | Lat. 11° 4' N / Long. 34° 7' 11" E | |

| Gulli | ||

| Amgar | ||

| Buud | ||

| Dungulawi | ||

| Latam | ||

| Joogdiik | ||

| Gosalbiit | ||

| Karaw | ||

| Goos Damib | ||

| Turuk | ||

| Daw (Baw on some maps) |

Lat. 11° 19' 39.88" N / |

|

| Baar | ||

| Sheer | ||

| Falloj | ||

| Ad-Dariyel | ||

| Bandallu | Water pools in Ad-Dariyel | |

| Galgug | ||

| Tonpoloori | ||

| Kosuga | ||

| Dandal | ||

| Mashruʿ bitaʿ gism | The name means: "project belonging to a unit (of the army)". | |

| Girinti Jua | All sorts of wild animals live there, including lions. | |

| Nasir | Lat. 8° 36' N / Long. 33° 4' E |

The route to the south-west:

| Place names | Coordinates, if found on map(s) or located by GPS (+ waypoint No.) | Comments |

| Buuk | ||

| Al-Ahmar (Sidak) | ||

| Wad Dabook | ||

| Silak | ||

| Malkan | ||

| Uulu | ||

| Fooj | ||

| Seeda | ||

| Zarzura | ||

| Donki Deleeb | ||

| Jamaam al-Gahnam | ||

| Kidwa | ||

| Dabanyaawa | ||

| Jine'oob | ||

| Maaber | ||

| Longushu | ||

| Daajo (Dago or Dago Post on some maps) | Lat. 9° 12' 6" N / Long. 33° 57' 29" E |

|

| Teebo | ||

| Mayyut (Mayot) | Lat. 8° 36' N / Long. 33° 55' E | |

| Uriel | ||

| Ng'elegel | ||

| Malwal | ||

| Jikaw | Lat. 8° 22' N / Long. 33° 46' E | |

| Nasir | Lat. 8° 36' N / Long. 33° 4' E | |

| Faashimi | ||

| Sonka | ||

| Akulla | ||

| Itang | Lat. 8° 12' N / Long. 34° 15' E | |

| Abol | ||

| Gambela | Lat. 8° 14' N / Long. 35° 15' E | |

| Bonga | Lat. 8° 10' N / Long. 34° 50' E | |

| Mangist Dirsha | ||

| Aloro | ||

| Giilo | ||

| Funyudo | Lat. 7° 40' N / Long. 34° 14' E | Also Pinyudo, Funyido, etc. – the location of a large refugee camp |

| Fashala |