Aufbruch mit Christiane, Getinet, Amanuel und Eshetu nach Anfillo. Anfillo ist der Distrikt, dessen größte Stadt Muggi heißt (siehe auch Karte 4 und Karte 10).

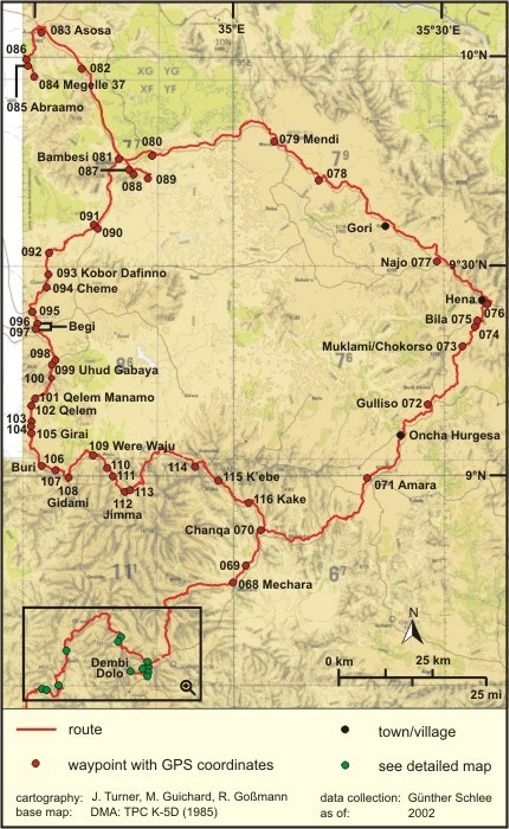

Karte 7: Von Dembi Dolo (Oromia Regional State) nach Asosa (Beni Shangul-Gumuz Regional State; Wegpunkte 029 - 035, 062 - 116)

Move mouse over the waypoints to see GPS coordinates.

Click where indicated to enlarge detailed map of smaller area.

Small town of Shabal (waypoint 031)

Amanuel directed us to a taj house. It is that of Harme Eshetu ("mother of Eshetu") – her own name is Zawditu. She looks like a northerner to me, but she speaks fluent Oromo with us (and equally fluent Amharic with Christiane). Getinet heard that she is from Wollo; our driver, who is also named Eshetu, heard her call her husband by a Muslim name.

When we ask Harme Eshetu whether there are any Mao in the area, she calls a young man for us. He is named Ambissa, is 31 years old, and comes from this place. He is unmarried. He explains to Getinet that he has not yet found the wherewithal to marry and is still looking for wage labour which would enable him to save money. Amanuel films the discussion with my video camera. Earlier, I had also taken some shots of Harme Eshetu and the interior of the taj house, which has a floor covered with split bamboo. Christiane, who has travelled widely in Ethiopa, says that she has never seen such a floor before. Here, this type of floor cover seems to be quite common.

Ambissa tells us that there are many Mao in the area, but that we should, rather, say Anfillo (which, in the older usage, appears to refer only to the region) because "Mao" has acquired a negative connotation. (Vinigi Grottanelli, writing in the 1930s, did not report that the term was in any way pejorative; see Grottanelli 1940.) Some years ago there was an attempt to gather Anfillo people together and to make them identify themselves as such, in order to gain recognition. These attempts were hindered and discouraged by the Oromo administrator in Muggi, Samuel, now deceased. Samuel said that the area was one of peaceful co-existence of different groups and that there was no use in stressing differences. Pressure was applied to the Anfillo to get them to declare themselves to be Oromo in the national census. (This is a remarkable contrast to the next higher administrative level, that of regional states, where the Oromo claim a separate state precisely on the grounds of ethnic difference.) Ambissa himself was a member of the group that sought recognition for the Anfillo.

Getinet asks Ambissa how one could tell the difference between Anfillo and Oromo on the street. In response, he says that the Anfillo can be recognised by their broad, flat noses and their dark skin – a description that fits him very well. We ask whether he can put us in touch with other Anfillo. Ambissa mentions his brother, who is a farmer in an area that is now mainly occupied by resettlers from Wollo. All these Wollo, he explains, are Amharic speakers; not a single one of them speaks Oromo. His family has been living there the whole time. The resettlers arrived in the Derg period.

We trace our way back for a short distance and then move off the main road to the east (exact location documented with GPS coordinates). We follow a track which once appears to have been cleared for a car, but which is now overgrown by high grass. There are large trees and in some spots dense growth of forest. In other spots there are coffee plantations under forest trees which have been left standing for shade. We come to a village with neatly fenced gardens, some with banana plants, and rectangular houses. It is called Fanno. Ambissa says he knows an old man here who is very knowledgeable about Anfillo history. He ascertains that he is around. So we no longer go to Ambissa’s brother.

The old man is named D’onka. We sit down under the protruding roof of his house in front of the entrance. Amanuel continues to hold the camera, but the sound recordings turn out to be quite bad. One reason is that rain sets in and makes noise on the corrugated iron roof.

Anfillo language: D’onka has heard stories set in the distant past when the "grandfathers" of the Anfillo did not understand any Oromo. But the Anfillo language is closely related to Kaffa. So some people even said: "Why don’t you just say you are Kaffa, why do you claim a different name?" I ask D’onka for some basic vocabulary – 'man', 'house', parts of the body – and do not recognise a single Cushitic root. He is the last generation to speak the language. The young only speak Oromo, and, to the extent that they have gone to school, some Amharic, although Oromo has become the medium of instruction.

Anfillo education: There are no university graduates among the Anfillo. The highest an Anfillo pupil ever got was grade 12. After leaving school, Anfillo have not usually found jobs, because they are discriminated against in the civil service. Many of them have gone back to agriculture.

D’onka says that he has three children. He is now living with his daughter and her children. Two of them go to school. One is in grade 4.

Anfillo migration: Out-migration is very low. D’onka is not aware of Anfillo in Addis Ababa or other major towns further afield. (This is basically confirmed by the census report of 1996 for the Oromia Regional State, p. 61 [see Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Central Statistical Authority, Office of the Population and Housing Census Commission, 1996]. But small numbers of "Maogna" speakers have been counted as far south as Boran). Apart from resettlement during the Derg period, immigration into the area is characterised by seasonal labour. This involves, mainly, Nuer from Gambella, who come for coffee picking around December. (Apparently, Nuer do more than just agricultural work. Christiane has heard in town, from Harme Eshetu, "The Nuer are like our children. They have raised our children for us", which implies employment as maids, nannies and houseboys. She was talking about the Haile Selassie period.)

Anfillo economy: The main cash crop is coffee. Money is used for taxes and settling debts at the shop. There is much borrowing in the neighbourhood. Maize is also produced for local consumption. Also root plants like potatoes and godare (Oromo term for taro – Colocasia esculenta – according to Tilahun Gamta’s Oromo-English dictionary, 1989) are grown and consumed locally. D’onka’s own field is some distance away from the village. Earlier, honey collection and hunting were the mainstay. The former is still important.

Anfillo marriage: When asked about how the Anfillo used to marry, D’onka’s first answer refers to sister exchange. There are clans (gos) which, to judge by his gestures, appear as localised, i.e., they are either co-resident descent groups or local groups with a descent ideology. He mentions some names and says which clans can intermarry and which cannot. Within a clan marriage can be permitted if the elders agree, on the basis of counting generations to the actually shared ancestors, that the relationship is distant enough.

Initiative is taken by the suitor. He should try to get in touch with the prospective bride himself. If she reciprocates his interest, both inquire about genealogies and possible obstacles to their marriage. A type of ring is given to the bride. There appears to be no bridewealth.

In recent times intermarriage with Oromo and others has become common. Marriage with Kaffa people from Jimma is even more acceptable, because they are nearly the same people. D’onka does not mention any specific cases.

Mao regional clusters: I explain that Grottanelli (1940) distinguishes two rather distinct groups of Mao, one in Anfillo and another much further north on the other side of the Didessa River. D’onka is aware of related people much further north. There is not much contact. He does not know how many there are.

Census: D’onka confirms Ambissa’s statement that there was pressure on the Anfillo to identify themselves as Oromo. The campaign for the recognition of Anfillo as a separate ethnic group was followed attentively and with disapproval by the Oromo.

|

Waypoint 032 | Lat. 8° 34′ 18.26″ N / Long. 34° 36′ 10.43″ E Muggi. Hoteela Shufeerotaa There is an inconsistency between the mapping provided here and some other maps. At the coordinates where I have located the town of Muggi, some maps give the place name "Gobi". |

Weiterreise nach Muggi. Wir kommen unter im Hoteela Shufeerotaa, im Chauffeurs-Hotel also. Die Besitzerin, so hat Christiane bald herausgefunden, stammt aus Tigre. Ein Helfer ist Wanderarbeiter aus Gojjam. Da alle mit dem Waschen von Laken beschäftigt sind, übernehmen Christiane und Getinet die Kaffeezeremonie. Christiane röstet, Getinet zerstampft im Mörser. Dadurch erregt er Verwunderung, denn das ist keine Betätigung für Männer. Ein Mädchen, das hier arbeitet, kichert verstohlen. Amanuel trägt zu der Zeremonie bei, indem er den Boden um Christiane mit Blättern von einem herumliegenden Zweig belegt. Ohne Bodenbelag ist es keine richtige Kaffeezeremonie. Die Aktion findet Anklang. Ein Gast bestellt eine Tasse von dem buna Ferenji ("Kaffee der Weißen").

Während ich meine Aufzeichnungen mache, gucken sich Christiane, Getinet und Amanuel den Ort an und knüpfen dabei über einen jüngeren Mann namens Nasir Kontakt zu einem alten Anfillo-Mann, der ihnen als sehr kenntnisreich über die Geschichte angepriesen wird. Der findet sich bereit, mit uns am nächsten Morgen ein Gespräch zu führen. Wir sollten ihm nur etwas "Fleisch" mitbringen.